Dr Sonia Ferdous Hoque, University of Oxford

One out of seven schools in Bangladesh’s Khulna district does not have a safe source of drinking water on premises. For those that have a waterpoint – usually a tubewell or rainwater harvesting system – the safety and reliability is uncertain. That is because there are no provisions to monitor water quality, breakdown and repair events, and quantity being used. The responsibilities for installing, financing, and managing waterpoints also vary depending on the type of school.

Who installs and manages waterpoints in rural schools?

The institutional and financing arrangement is more streamlined for government primary schools than for secondary or non-government schools. For government primary schools, capital investment for WASH facilities is financed through the Primary Education Development Program (PEDP) – a multi-donor and government funded project supporting the primary education sector since the early 2000s. The installation process is led by the Department of Public Health and Engineering (DPHE) – the national agency mandated to provide rural water services. Once an infrastructure is installed, expenses for minor operations and maintenance can be funded through the school budget, which is extremely limited, usually between Tk 50,000 and Tk 70,000 (USD 500 – 700).

Secondary schools often have integrated ownership, meaning that the government pays for staff salaries while other costs need to be covered through tuition fees. Thus, waterpoints in secondary schools, as well as in private and NGO schools, are installed through school funds, donor-funded projects, and funds from union council or local MP, and in some cases by DPHE, if there is no boundary wall restricting access to the community.

When does provision of safe drinking water become a challenge?

Under the above arrangements, water supply is not a problem for areas where fresh groundwater is available. Schools in such areas, usually in the northern part of the district, in fact, have multiple tubewells, upgraded with submersible pumps and internal plumbing. Annual repair and maintenance costs are estimated to be Tk 2100 (USD 21).

But good groundwater is not available everywhere due to high levels of salts or iron. The alternative option is rainwater harvesting, but the availability is restricted by tank size and roof catchment area. In Dacope, one of the nine upazilas (sub-district), many schools have high storage capacities (>10,000 litres) owing to multiple donor-funded projects operational in that area for decades. But schools in other upazilas usually have much lower storage, lasting only a few months. Bacterial contamination is a major problem unless the catchment and tanks are disinfected thoroughly pre-monsoon.

Other technologies, like reverse osmosis plants, small piped schemes and pond sand filters, are available in small numbers (about 3% of schools). These are costly and complex technologies and often risk being non-functional after a few years due to lack of maintenance.

When schools do not have any drinking water source, either during the dry season or at all times, students and teachers have to manage on their own. Teachers pay out of pocket to purchase vended water, and students may bring water from home. In many cases, children end up using unsafe sources like shallow tubewells or fetch it from nearby households where available.

How is REACH driving change to provide safe water services in schools?

Since 2016, interdisciplinary research in Bangladesh’s coastal observatory have advanced our understanding of coastal hydrogeology, public and private infrastructure investments, water quality risks and people’s water use behaviour. REACH has actively engaged with UNICEF, DPHE and the Local Government Division (LGD) to support the government’s commitment in addressing water supply challenges for unserved rural populations.

The SafePani model emerged from these science-practitioner collaborations. The aim is to reform institutional design and financing mechanisms with a view to shift responsibilities from individual school administrators or waterpoint users to a professional service provider, similar to the roles of urban water utilities.

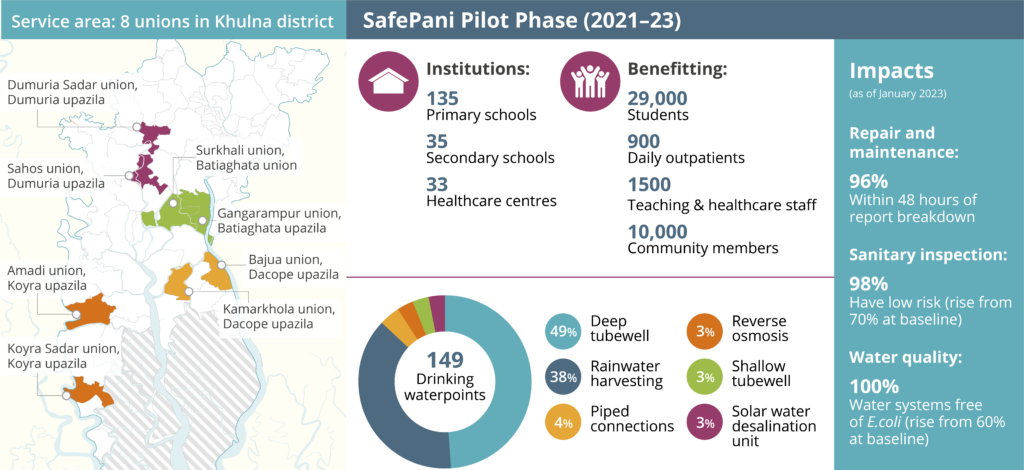

Since late 2021, the model is being piloted in 171 schools, 33 healthcare centres and 4 community schemes across eight unions of Khulna district. The pilot work built local capacity and demonstrated the mechanisms and outcomes of professional water service delivery.

How does the SafePani team deliver professional water services?

The SafePani team in Khulna, led by HYSAWA, comprises dedicated staff for water quality testing, government and community liaison, engineering works and project management. They provide the following services to ensure water safety and reliability in schools.

First, all existing water infrastructure are rehabilitated to a high standard following baseline technical assessments. This may involve constructing or repairing tubewell platforms and drainage systems, or mending leaky taps or pipes and replacing filter media for rainwater harvesting systems.

Second, the team ensures that all water points are repaired promptly upon identification of breakdown or maintenance need. These are usually reported to the SafePani team by the schools, or detected during regular site inspections.

Third, water safety is ensured through sanitary inspection, baseline tests for arsenic, manganese and chloride, and seasonal tests for E. coli, followed by prompt disinfection of sources upon detection of faecal contamination.

The field activities are reported through quarterly meetings to a National Steering Committee, led by the Additional Secretary of LGD, and a District Working Group, led by the Deputy Commissioner of Khulna district. Where needed, the committee directs the responsible authorities to take action.

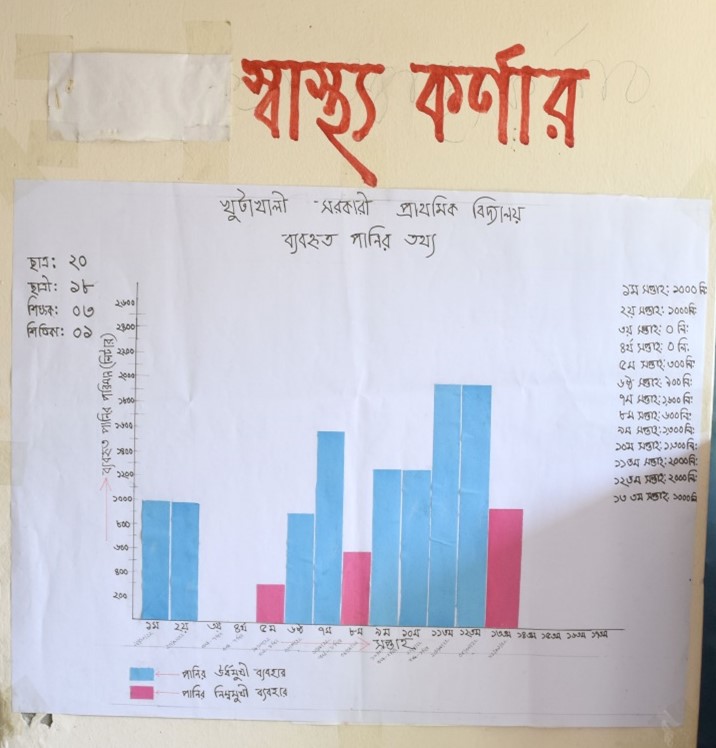

The team is also developing an online data management system to report on key performance indicators like water quality, volumetric use, breakdown and response times, and costs. Such information systems can enable governments and third parties to monitor progress on key indicators of SDG 6.1 – quality, quality, reliability, and affordability.

How can we scale-up the SafePani model and sustain it beyond REACH?

With ongoing commitment from the government, there is significant potential to upscale the model at the district level. Our estimates show that safe and reliable drinking water services can be ensured for less than USD 1 per person per year, directly benefitting 320,000 students in 1700 schools and 9000 daily outpatients in 300 healthcare centres.

To move from a project-funded pilot phase to sustainable services at scale, we are exploring suitable contracting arrangements between the government and a professional service provider operating within an exclusive area. Financing can involve the government allocating a proportion of the required funds, with the remaining being funded by an external donor based on performance indicators. Such blended finance is gaining increased traction to address financing gaps in the water sector.