Nancy Balfour, Centre for Humanitarian Change

Over the past three years, research led by Nancy Balfour on pastoralist women in Samburu county, Kenya, has explored the links between women empowerment and water security. Her research sheds light on the drivers of water stress and on the factors that enhance their resilience. In this blog, she shares key findings, and reflects on their implications for the wider water sector.

Pastoralist women bear the burden of water insecurity

During the last three years, we have been working with pastoralist households in Samburu County in Northern Kenya. These semi-arid areas are experiencing the combined effects of climate change, population growth and extreme climatic events. During this period, extreme drought and extreme rainfall and flooding have resulted in many families dropping out of pastoralism and settling around the urban centres, relying on occasional labour and trade (often charcoal selling). The families that are ‘hanging on’ in the rural areas are equally vulnerable, with their welfare dependant on terms of trade between livestock and food items. These families can best be described as pastoral orphans.

Our earlier studies highlighted the fact that women bear the greatest burden in these families, as they are responsible for providing water and food, and caring for children as well as caring for small animals left at the homestead. Their priority, and the task that takes the most time and effort every day of the year, is fetching water. The distance they have to travel means that most households have only a minimum amount of water to use, and women suffer considerable stress over whether there will be enough water for all their critical needs.

In a sample of over 700 households in rural and peri-urban areas, the average water use per person was below minimum humanitarian standards (15 litres per person per day) across both wet and dry seasons. For the majority of the households, the daily task of collecting water takes more than two hours. Women’s resilience and fortitude in the face of this physical and mental burden is extraordinary and much of their ability to cope is down to their social networks and the way women support each other.

Quantifying water insecurity in rural and peri-urban households

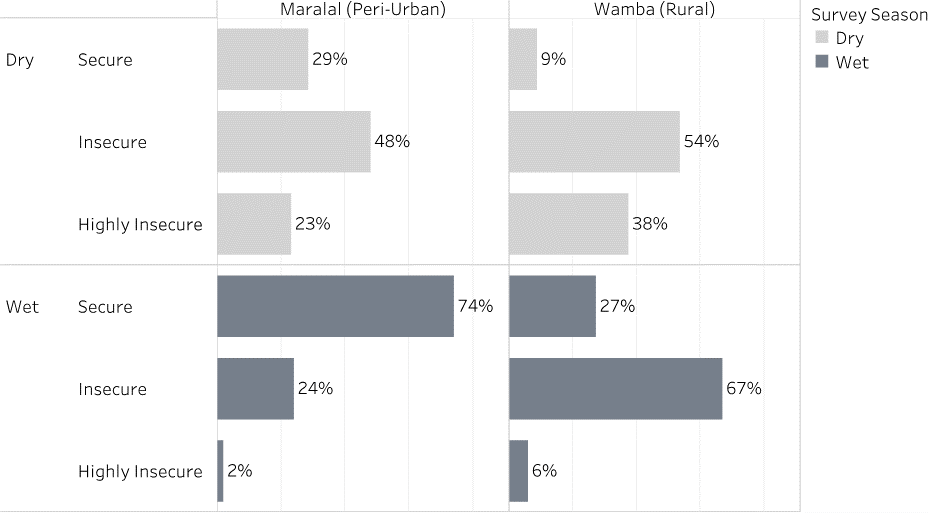

In our studies, we have attempted to quantify the level of water insecurity of these households using a scale of household water insecurity. Measuring water insecurity in this way helps to identify particularly water stressed communities and individual households. Using this tool, more than 90% of rural, pastoralist households are either water insecure or highly water insecure in the dry season. This is not surprising given the extreme environment they live in but what is more surprising is that more than 70% of the peri-urban residents are also water insecure.

This level of water insecurity raises some critical policy questions about whether investment in water development is either adequate or appropriate to provide climate-proofed and resilient water services. It also raises questions about why women with this level of water responsibility are routinely excluded from decisions related to water development. The fact that women are responsible for collecting domestic and livestock water, water storage and managing water supplies for the household implies that initiatives to improve household water security should be addressed to women (individually or as a group) rather than through the community or through male-dominated water committees.

Links between food and water security

Other important policy implications relate to the impact of water insecurity on the nutrition and food security of families in these fragile areas. How can women who spent up to five hours a day fetching a small quantity of water possibly care for their health and nutrition and that of their children properly? This is a workload issue, not ignorance of hygiene practices!

Considerable investment is being directed to reducing child malnutrition and food insecurity but this continues to focus on treating the symptoms and not addressing the root causes. Why isn’t household water insecurity the main focus of development programmes, instead of a side issue?

The importance of social capital and safety nets

On a more positive note, women do seem to be finding their own ways to manage their water situation through social capital and safety nets. Our studies show that during periods of severe water insecurity and when individual women are indisposed, it is other women that come to their aid by helping with the collection of water and even ‘loaning’ water.

A woman’s membership of women’s groups and her ability to mobilise her network in such groups to support her during her time of need is critical to keeping enough water in the household. Similarly, ensuring that access to cash is controlled by the women in the household during times of stress allows them to pay for water and/or transport to ease the workload.

Reflections for the water sector

Our study provides evidence of a water security crisis in one community in Kenya, but similar patterns are seen across many arid and semi-arid parts of East and the Horn of Africa. Measuring water insecurity alongside routine assessments of nutrition and food security will help to highlight this as a key factor in persistent, seasonal stress but the water sector needs to step up and raise its profile in both domestic and international funding decisions to ensure targeted, appropriate investment in water security.

Our findings on the dimensions of household water insecurity suggests that climate-proofing water infrastructure development is only part of the solution. Investment in systems to provide sustainable water services and in strengthening safety nets at community and household level is equally important.

Gendered dimensions of water security risk for pastoralist households in Northern Kenya is one of 5 Accelerated Projects funded through REACH Partnership Funding.