Meleesa Naughton

Many countries are looking to expand rural water services and improve service levels for people living in small towns and rural areas by investing in small, decentralised piped water services. Francophone West Africa has a long history of delegating water services (usually piped) in small towns and rural areas to professional operators, both public and private.

The RWSN Secretariat in partnership with the REACH programme spent the last year investigating the experience of the delegation of rural water services and the drivers behind recent rural water policy reforms in several countries of francophone West Africa. We did a detailed desk review, and spoke to 25 experts in rural water sector in the region to understand why and how rural water policy reform happened, and what lessons can be drawn from their experiences in delegating rural water services to professional operators.

A word of caution – it is extremely difficult to try and synthesize this experience of six countries (Benin, Burkina Faso, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, and Senegal) in a report, let alone a blog, without oversimplifying the many complexities of each case. In this blog I will share my personal learnings from the research , and I encourage you to read the full report (available here in English and French) to get the full picture.

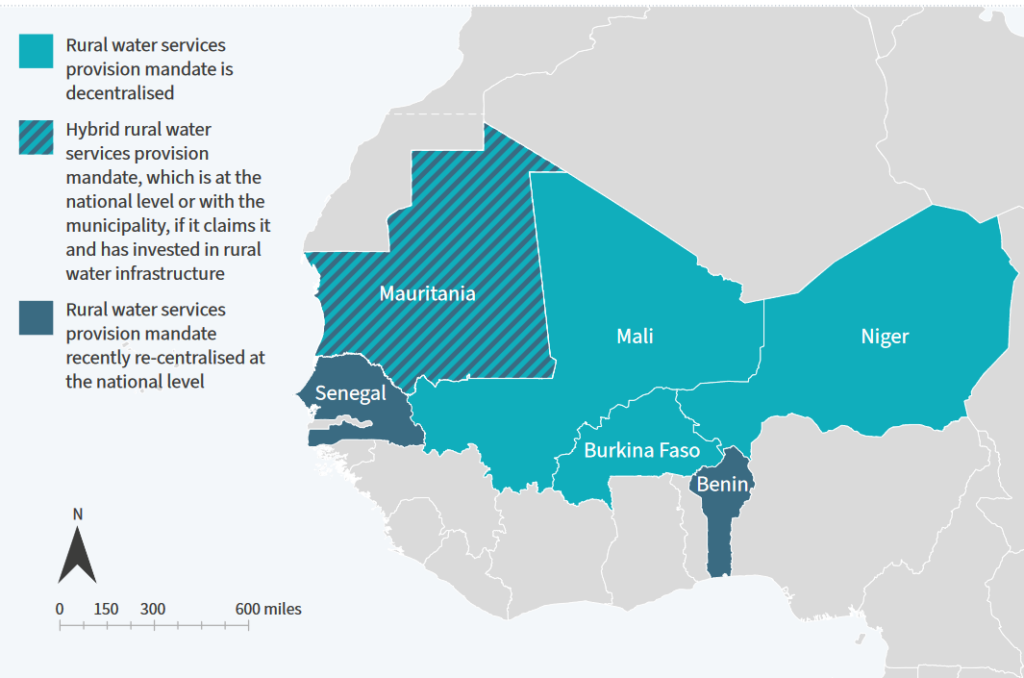

Looking at rural water policy over the past 30-40 years, we see several waves of reform in these countries, with a “push-and-pull” effect for the mandate for rural water services between central and local actors. More recently, several countries have recently launched rural water reforms where the central State has “taken back control” from local government or community-based organisations to establish a central rural water authority and delegate rural water services at a wider regional level. Other countries in the region and beyond are watching and thinking to understand whether this is a good idea to emulate.

Rural water service authorities in the countries under review. Source: RWSN/REACH (2023)

It will not come as a surprise that delegating rural water services to a private operator is not a universal alternative to community-based management. In many countries, there is a gap between theory and practice, with alternative models for rural water services delivery co-existing with informal arrangements, where services should have been delegated.

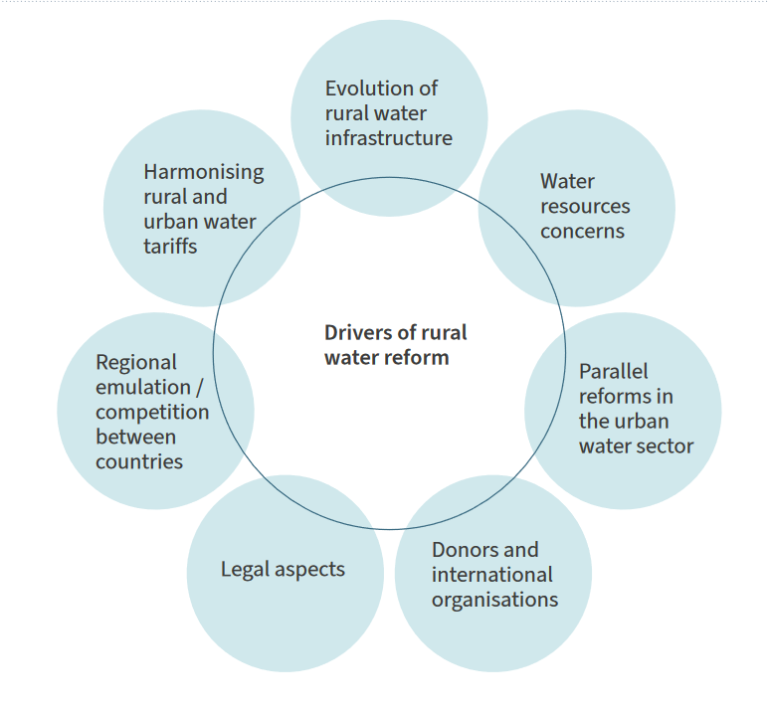

So how and why do these rural water reforms take place? The figure below gives a sneak preview of the drivers behind rural water reform in the countries reviewed. Of those, donors and international organisations were identified as catalysts for the promotion and replication of the delegation of rural water services in the sub-region, but not always for the reasons you might think.

Overview of drivers for rural water reform in the countries under review. Source: RWSN/REACH (2023)

Increased efficiencies and better performance of service provision are also a key factor for motivating these reforms. West African countries have experimented with clustering rural water infrastructure to delegate rural water services at the scale of several municipalities, a district or a region. When the mandate for rural water services rests at the local level, this can be done by grouping several local authorities, through Design, Build and Operate contracts (DBO) and inter-municipal arrangements. In practice, there are few DBO contracts and all have been supported by donors; and inter-municipalities are still the exception in the sub-region and are often victim of political infighting or contractual disagreements.

When the mandate for rural water services rests at the national level, services can be delegated at a much wider regional scale, as in Senegal, Benin and Mauritania. While these reforms are still ongoing, some lessons learnt can be shared, in particular around the need to acknowledge the tension between political decentralisation processes and a partial or complete re-centralisation of rural water services mandates; and to recognize the advantages and the risks inherent to clustering rural water services, which may have been under-estimated in some cases (see figure below).

Risks and benefits linked to clustering / aggregation of rural water services (RWS). Source: RWSN/ REACH (2023)

Experiences with re-centralisation/ decentralisation of service authorities, and the delegation of rural water services at local or regional level, should be analysed carefully to understand their impact on service quality and population coverage. An institutional framework that monitors clear targets and promotes a transparent framework for accountability and dialogue on performance will enable the pathways to be corrected if necessary.

While no unique solution seems either plausible or pragmatic for all countries in West Africa, clearer evidence of what works and why is central to determining future policy and investments. This study identifies some of the key questions in this ongoing debate, which need further reflection:

• Will the move to re-centralised rural water service authorities improve financing, performance monitoring and asset management?

• Where decentralisation is ongoing, what will the role of local stakeholders (including local government) be in countries that have recently re-centralised the rural water sector? Will they be able to hold service authorities and operators accountable?

• In contexts where it has been decided not to subsidise rural water tariffs, how should water services delivery be funded sustainably while ensuring equity between rural and urban residents?

• Will regulation evolve to ensure the sustainability of rural water services under delegation?

• In contexts where international expertise is needed to deliver universal rural water services in the short-term, how will local capacity be developed to ensure the sustainability of rural water services in the long-term?

Key takeaways from the study

• Rural water operators will be able and interested in providing rural water services if the financial viability of the services to be delegated is assured, and risks are adequately shared between the operator and the delegating authority. For this, the type, size and scope of rural water services to be delegated, the type and length of the delegation contract, and contractual modalities need to be optimised.

• A clear political, institutional, regulatory and legal framework, which enable long-term contracts and give operators some visibility and clear contractual terms, is essential to the delegation of rural water services both in centralised and decentralised mandates.

• Transparent financing and subsidies, including for O&M when tariffs are below the operational cost recovery level, may be needed to ensure the acceptability of services by rural populations.

• The public services delegation mechanisms that work best are those that are subject to a regular framework for dialogue. Regulation, data and monitoring still require improvement to inform decision-making for rural water services. Whether anchored at national or local level, regulation should be based on principles of efficiency, transparency and accountability, and address local water users’ concerns.

• The professionalisation of rural water services provision depends on the existence of qualified operators interested in working in rural areas (public or private, local or international). Reform efforts must consider local operators’ experience to avoid the perception of “dispossessing the country of local capacity”, which also has an impact of social acceptability and the sustainability of water services.

About the author: Meleesa Naughton is the deputy director of the RWSN Secretariat and the lead author of the REACH/RWSN publication on the performance and prospects of rural drinking water services in francophone West Africa.

Photo credit: Johannes Wagner – a solar-powered water kiosk in Moribala, Mali.