Dr Sonia Hoque (University of Oxford), and Md. Monirul Alam (UNICEF Bangladesh)

This blog presents the SafePani model, a new institutional framework for rural water service delivery in Bangladesh. You can read the REACH Working Paper titled ‘Policy reform for safe drinking water service delivery in rural Bangladesh’ by Hope et al. and the policy brief for more information.

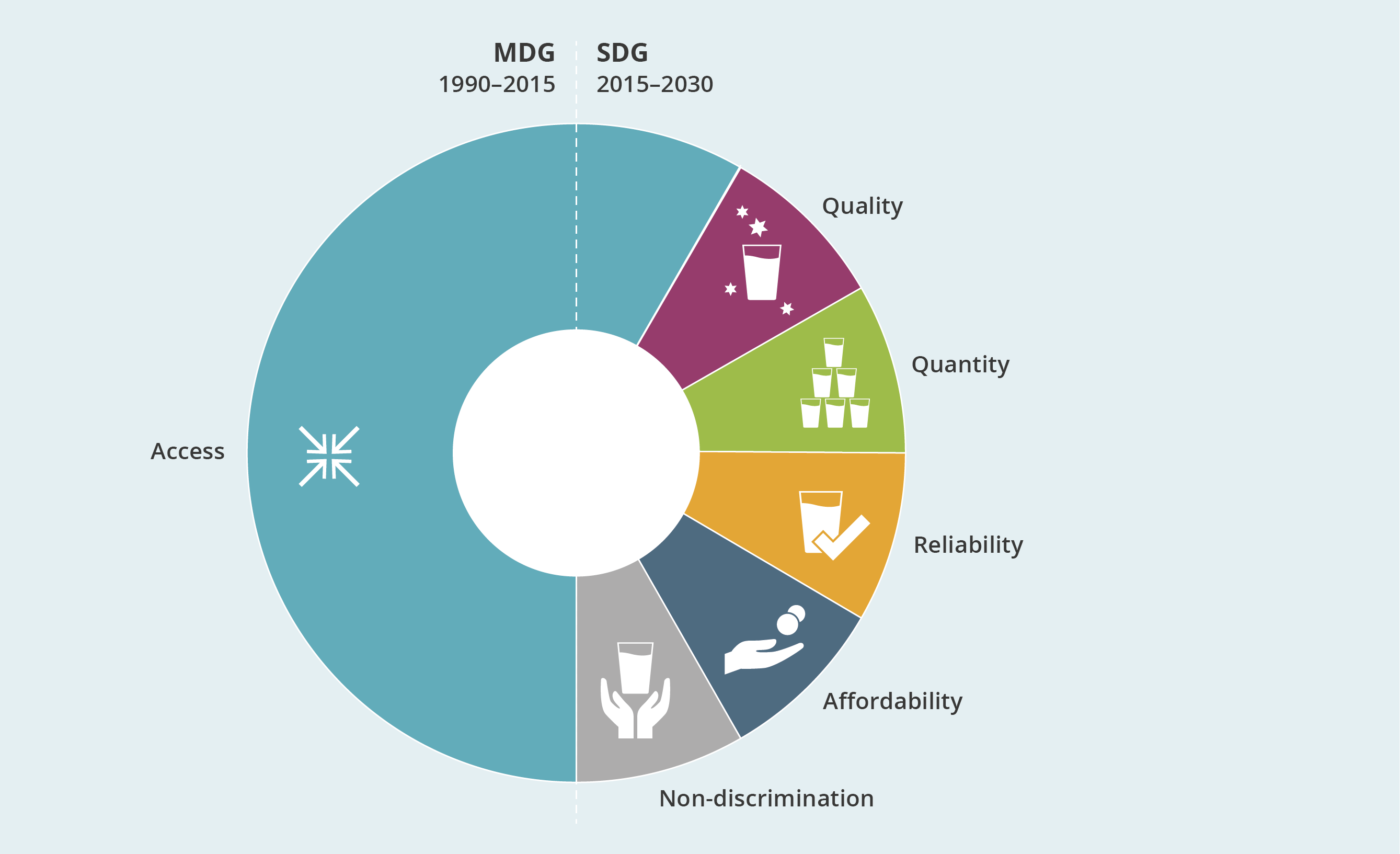

Existing rural water service delivery in Bangladesh focuses on increasing waterpoint ‘access’. Usually, this is achieved by installing water supply infrastructure paid for by public funds and external assistance, with periodic project-based mapping of waterpoints and nationally representative surveys providing estimates of sector performance. The expanded focus of SDG 6.1 entails a shift in policy and practice from increasing ‘access’ through infrastructure development to a ‘service’ delivery approach that addresses these risks in water quality, reliability, affordability and social inequalities (Figure 1).

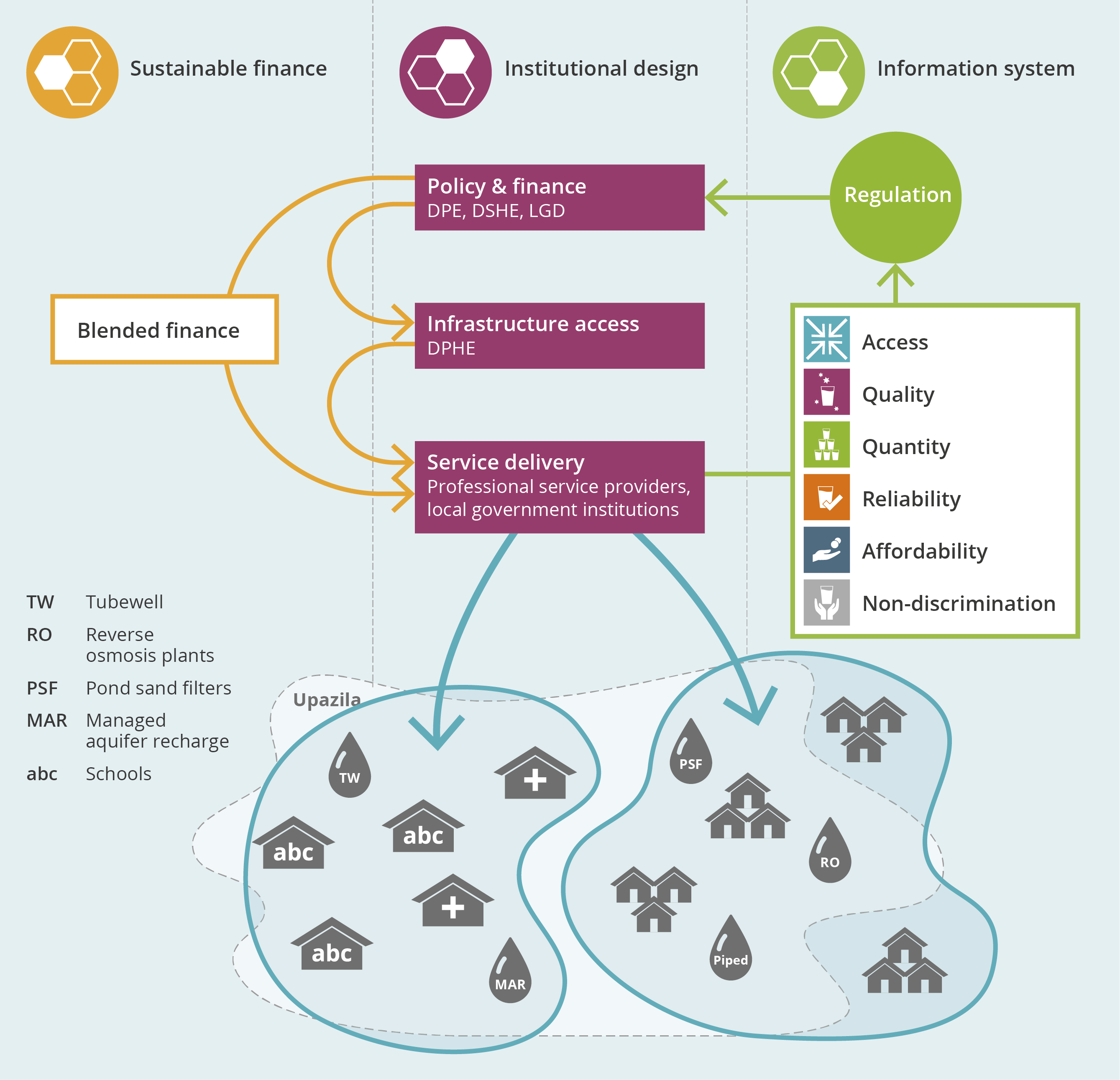

As the Government of Bangladesh sets out to revise the 1998 National Policy for Water Supply and Sanitation, we propose a new institutional framework – the SafePani model – that aims to strategically leverage public and private funds, with timely and accurate information systems to support independent monitoring and regulation of water service delivery.

The design of the SafePani model is informed by collaborative work of the REACH programme, led by UNICEF, the University of Oxford, Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET), and the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Diseases, Bangladesh (icddr,b), with support from the Water Supply Wing of the Local Government Division (LGD), Department of Public Health and Engineering (DPHE), Directorate of Secondary and Higher Education (DSHE) and the Directorate of Primary Education (DPE) of the Government of Bangladesh.

Interdisciplinary research in the coastal zone (Khulna) and central plains (Chandpur) reveals intersecting challenges: a) hydroclimatic and water quality risks, b) public financing and private enterprises, and c) social and spatial inequalities. Hydroclimatic risks include spatial variation in groundwater salinity and arsenic, seasonal variation in rainfall, and episodic shocks from cyclones and floods. Gaps in public investments in water supply infrastructure, coupled with operational and maintenance challenges, have created demand for private services by informal water vendors and fueled self-supply investments. Household water use behaviour, in terms of their day-to-day choice of water sources and expenditures, reflect significant geographical and wealth inequalities in access to safe water.

Future policy has an opportunity to not only recognise the role of private investments from households and small water enterprises, but also create new service delivery models with sustainable financing and regulation at scale. The SafePani model proposes reforms in three areas – institutional design, information systems and sustainable finance (Figure 2).

Institutional change will entail responsibilities to be clearly allocated and regulated from national to local levels. Information and monitoring systems will allow progressive improvement of the quality of water services in terms of safety, functionality, and affordability. Service delivery models can be designed to network infrastructure at the right operational and political levels. Policy changes can make provision for exclusive service areas, and independent regulation and enforcement to ensure no one is left behind.

Financing service provision will require public and private funds to be more effectively combined to deliver results. Information systems will improve the allocation of funding and can attract new sources of funds based on performance. User payments will be central to financial sustainability with preferences for onsite infrastructure, such as piped water to homes and facilities, requiring tariffs to be affordable for all water users.

The SafePani model will be piloted in late 2021 in three unions of Khulna district, where a professional water service provider will take over operation and maintenance responsibilities for piped schemes, pond sand filters, managed aquifer recharge, and desalination plants. Water quality will be regularly tested at locally purpose-built laboratories. The service provider will also generate regular data on performance indicators that can be shared on publicly accessible information systems.

Such verifiable data can potentially unlock results-based funding to reduce dependency on donor funding in the future. Testing the SafePani model will require progressive reforms in policy, including acknowledging the roles of self-supply and water enterprises, identifying professional service providers as responsible entities, and establishing an independent regulator for monitoring and enforcing performance targets.

Further reading:

Hope, R., A. Fischer, S.F. Hoque, M.M. Alam, K. Charles, M. Ibrahim, E.H. Chowdhury, M. Salehin, Z.H. Mahmud, T. Akhter, P. Thomson, D. Johnston, S.A. Hakim, M.S. Islam, J.W. Hall, O. Roman, N. El Achi, and D. Bradley (2021). Policy reform for safe drinking water service delivery in rural Bangladesh. REACH Working Paper 9, University of Oxford, UK.

Hoque, S.F., Hope, R., Alam, M.M., Charles, K., Salehin, M., Mahmud, Z.H., Akhter, T., Fischer, A., Johnston, D., Thomson, P., Zakaria, A., Hall, J., Roman, O., El Achi, N., and Jumlad, M.M. 2021. Drinking water services in coastal Bangladesh. REACH Working Paper 10. Oxford, UK: University of Oxford.

McNicholl, D., Hope, R., Money, A., Lane, A., Armstrong, A., Dupuis, M., Harvey, A., Nyaga, C., Womble, S., Allen, J., Katuva., J., Barbotte, T., Lambert, L., Staub, M., Thomson, P., and Koehler, J. (2020). Results-Based Contracts for Rural Water Services. Uptime consortium, Working Paper 2.