Dr Katrina Charles, REACH Co-Director, University of Oxford

As the COVID-19 pandemic has escalated in recent weeks, there have been increasing reports on the differential impacts. The evidence for the impact on the elderly was established early on. Different death rates by gender and ethnicity have been reported, but it is not yet known if these are due to genetic differences, or are related to differences in exposure.

Increasingly we are hearing reports from major cities, such as New York , Barcelona, and London, that point towards inequalities in the spread of the disease. Some of the common themes often relate to wealth, types of employment that increase risk, and living in crowded conditions. This has focused concerns about the potential for the spread of the disease in informal settlements in many countries, where social distancing is more of a challenge[.

COVID-19 is not waterborne, but the importance of hand hygiene highlights that it is a water-related disease. The benefits of WASH to reduce the spread of respiratory diseases are well known. But more than that, water insecurity can limit people’s ability to practice social distancing. In these aspects, the inequalities in water insecurity represent unequal risks in this current pandemic.

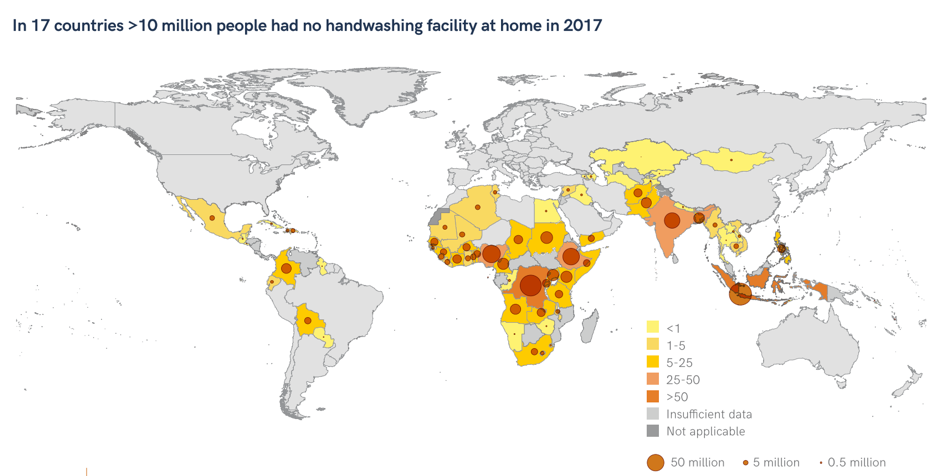

Handwashing is a habit we have all had to improve, but approximately 40% of the population globally has come into this pandemic without access to a handwashing facility with water and soap at home. While the data for this is limited, the Joint Monitoring Programme access wheel highlights the biggest gaps are in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Source: WHO/UNICEF JMP

Handwashing will not just be a challenge at home. The limited data available on handwashing facilities in healthcare facilities suggests fewer than 25% in rural areas have reliably available water, soap, and hand-drying materials. In a recent webinar WHO led on water in healthcare facilities, the repeated questions about how to reuse handwashing water highlighted the challenge that healthcare providers face without sufficient water supplies.

Water access can be a challenge during lockdown if water is not available on premises. This is the case for 25% of the global population (2019 JMP Report); many of those without water access on premises live in Sub-Saharan Africa, where 50% of urban and 88% of rural households lack water access on premises. For these households, and particularly the women, this means that water needs to be collected or bought from vendors. This is normally a daily activity, without the possibility to store a week’s worth of water. In some countries, lockdown has resulted in long queues and crowds gathering to secure water. With increased handwashing, even more water will be required to be collected.

Governments and NGOs are making rapid changes to policy and practice to help the vulnerable and address these inequalities. Kenya is rapidly increasing water access in informal areas of Nairobi. Ghana has announced free water for all for three months. A global network of practitioner organisations working on water security issues are quickly shifting their priorities to focus on the pandemic in Africa and Asia, including initiatives under the leadership of WHO, UN-Water, UNICEF, as well as IRC among others.

While these measures will provide some immediate relief, they are unlikely to address the fundamental drivers of vulnerability. The virus is exposing, perhaps more than ever before, the impact of these WASH inequalities on health and the economy more widely. Failing to address them will compromise the resilience of WASH systems in the long run, making societies more vulnerable to future shocks, including from a future re-emergence of COVID19 and from other health emergencies, as well as climate change.

This is why, at REACH, we are committing to working towards understanding and addressing inequalities in water security, making this a core theme driving our work across all countries – not only during the pandemic, but throughout the duration of the programme. As the world responds to the COVID-19 pandemic, REACH will work to understand and address more sustainable policy and practice through our partnerships with government, academia and the private sector. More vulnerable people have more constrained choices by structural inequalities in access to safe, reliable and affordable services. The crisis presents an opportunity to reveal and respond to these inequalities.