Professor Katrina Charles, REACH Director

More than two billion people – a quarter of the world’s population – are without access to safe drinking water at home. The water supplies they rely on are commonly contaminated with faecal bacteria, making it more likely that pathogens such as typhoid and cholera are present*. Many more are contaminated with chemicals known to be harmful, such as arsenic and fluoride, on which we have less data.

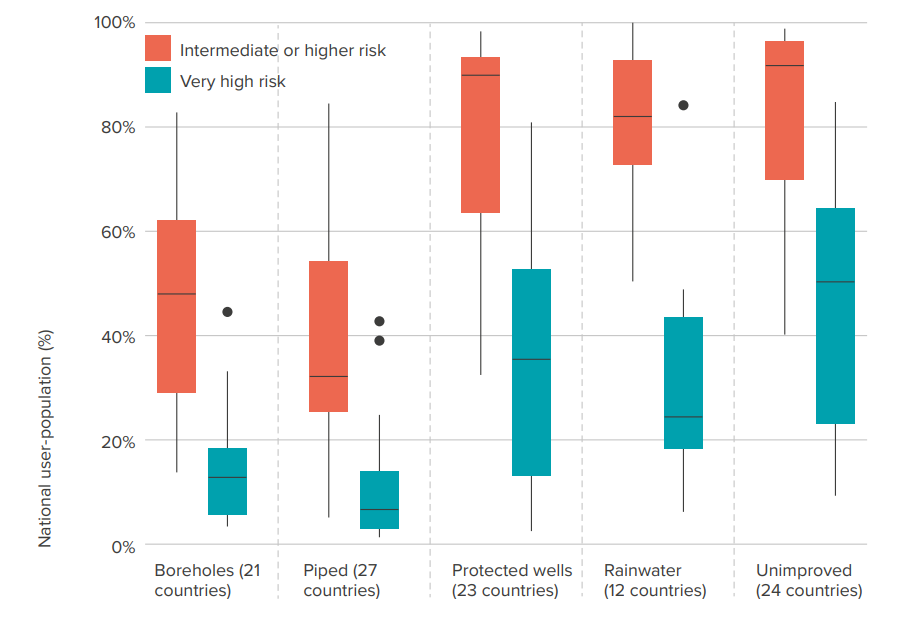

For decades it has been assumed that boreholes will provide safe drinking water, and so they have been built by governments and NGOs to provide ‘safe’ drinking water to communities across the world. The water they provide is usually safer that drinking untreated river water, but it is far from safe. WHO/UNICEF data shows that in some countries, as many as 90% of boreholes are contaminated (Fig 1). One of the key things that is lacking is management of these water systems to ensure the safety of the drinking water. Indeed, funding for water safety actions is often constrained as many contaminants cannot be sensed directly by users, so they don’t recognise the value of the additional work to improve safety.

Figure 1: International data on drinking water quality shows that improved water supply technologies often don’t provide safe drinking water. The orange box-and-whisker plots show the percentage of national populations that are exposed to faecal contamination across five infrastructure categories, this includes any water sample at the point of collection with 1 or more faecal indicator bacteria per 100mL. The green plots show those exposed to a very high level of faecal contamination risk: samples containing more than 100 faecal indicator bacteria, a smaller proportion of the population but still significant across all infrastructure categories.

Source: Bain et al, 2021.

The problem extends to water in schools and healthcare facilities. We know that access to improved water in these institutions is lacking, but there is no global data on the quality of water being supplied to pupils, patients and staff. The health impacts for people who use unsafe water can be severe, especially for children and vulnerable patients. However, many health impacts won’t necessarily be immediate; they may experience no more than occasional diarrhoea as they build immunity to the different microorganisms, but over time the pathogens and chemicals will contribute to slowing their growth, potentially impacting their health and future chances in life.

Improving safety of drinking water services

Across the REACH team, we have been researching how to improve water safety across several dimensions. We have developed fit-for-purpose laboratories to ensure water service providers have access to operational data on water quality to inform their actions. We have explored variability in water safety risks across geographies and systems, including microbiological and chemical risks, considering climate risks and risks to the most vulnerable. We have worked closely with communities, service providers and governments to understand how people use information on water quality risks to advance water safety.

We co-developed the SafePani model with the Government of Bangladesh to deliver operation and maintenance and water safety services to schools and healthcare facilities through professional service providers. We have worked with a professional service provider in Kenya to embed water quality monitoring and explore how a professional service delivery model including water quality monitoring can be extended to schools.

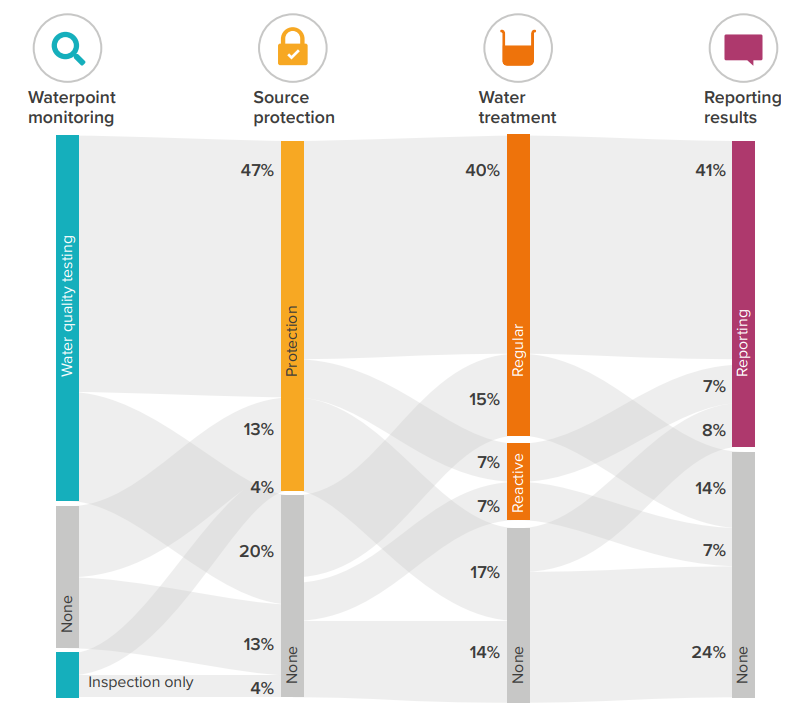

Through these we have demonstrated models that support water safety improvements in rural areas across multiple geographies. With Uptime and RWSN, in a global survey of professional service providers, we showed that whilst they are almost universally undertaking some water safety activities, it is not consistent (Fig 2). Based on this research and experience, we have worked with Uptime to develop a new approach for results-based funding for professional service providers to incentivise water safety activities.

Figure 2: Water safety activities among service providers are common but not consistent: Waterpoint safety activities reported by 257 service providers across the world. Source: Nilsson et al, 2021.

A new results-based approach to accelerate safe drinking water services at scale

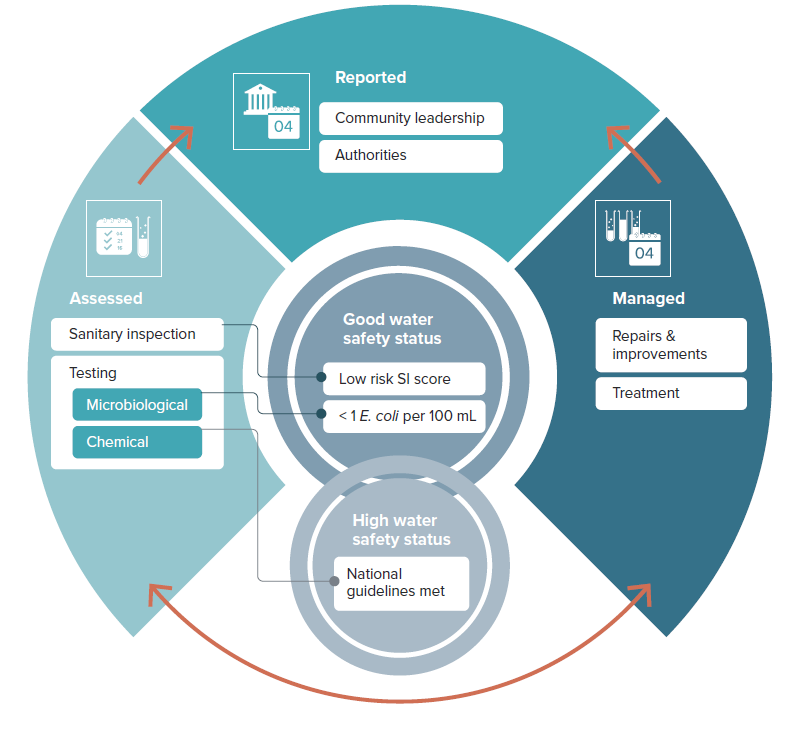

Figure 3: Improving water safety status through assessment, reporting, and management. Source: Charles et al., 2023

The approach (Fig 3) builds on water safety planning and the forthcoming WHO Guidelines for drinking-water quality: small water supplies targeting three domains of assessment, reporting and management to ensure good water safety status.

Over the next year, we will be working with Uptime as they pilot the approach with several partners. By doing so, we hope to increase recognition of the water safety work that professional service providers are already doing, and provide incentive payments for assessment, reporting and management to help improve water safety.

*Why don’t we hear about outbreaks of these diseases all the time in under-resourced countries if 2 billion people lack access to safe drinking water? A combination of weak health surveillance and a build up of immunity. People build immunity, so while that immunity might wane it will do so at varying rates making infections a chronic issue rather than a big spike of cases that would easily be picked up by a weak health surveillance systems. In developed contexts, where there is good health surveillance with low levels of immunity, we occasionally see outbreaks of waterborne disease where 40% of the population get ill from a single type of organism but because of the work done to monitor, treat and manage a safe water supply, and to manage the sanitation systems too, these are rare.

Photo credit: Luftor Rahman